Between the Blood and Drought

Between the Blood and Drought

Elise Tegegne

On Mothers Who Miscarry

As far as anyone can remember, Addis Ababa shimmered in sunlight for nine months of the year. Besides the small rains (a short rainy season in February of the ferenge calendar) the capital of Ethiopia glinted dry under a taut dome of blue. Then from about June to August, rains drenched the mountainous capital. Jangling mini-buses, indigo jacaranda trees, wheelbarrows mounded in moons of orange— all baptized slick and shiny in sky water. Tiny cafe tables cluttered in cups of strong coffee darkened as the clouds tore in two. Sometimes the lights would vanish. But September birthed a new year.

*

The second time I held a positive pregnancy test I felt, above all things, a giddy joy. What did it say? my husband asked, still wrapped in nighttime blankets. I could not force words from my mouth. Sputtering . All I could do was hold up two fingers like a peace sign. I was trying to say that our children now numbered two— that I held our second baby in my body (the first was still asleep in his crib down the hall). Finally, eyes shimmering , I spoke: I’m pregnant. And he pulled me into his chest.

*

Before, the Addis sky held fast. Clouds puffed into the shapes of cats and castles and disappeared without releasing one drop. But lately, the rains have been leaking throughout the year. Not just during the small rains and the rainy season, but even in May: the hottest month now strangely cooled.

Everyone’s confused, my husband says, after a recent call to his family. They live in a palm-shadowed compound near a roundabout clotted with motorbikes, fruit stands, buses, vendors hawking traditional cotton shirts embroidered in gold and crosses.

Addis isn’t the only part of Ethiopia grappling with shifting weather. In the south, the long rainy season has shortened, while the short rains have intensified. These aberrant patterns have birthed the longest and most severe drought on record. Fifty million people in the Horn of Africa have been touched: wells desiccated, bellies scraped clean, teff fields dead before the seeds have had the chance to sprout.

*

From the beginning, something didn’t feel right. My womb would tighten like a fist, flex like a hand preparing to punch. And one evening, about a week after my positive pregnancy test, I noticed brown blotting my tissue paper. I was leaking. Body trembling , I returned to the kitchen where I had been preparing dinner. Water boiled, the knife lay waiting, and my mind could not register my toddler on the floor tearing open a box of screws, ripping it to unusable shards.

*

Most Ethiopians I know dread the rainy season, just as most Americans I know dread the winter. The power and (ironically) water often sputter out. Skinny jeans and cotton netelas soak in minibus lines stretched for blocks. Chill grips a city without furnaces.

When I taught at an international school in Addis, I had the luxury of enjoying this season. For me, the rains meant the near end of another exhausting school year, extended mornings with a cup of instant coffee in the teachers’ lounge, an emptied calendar with wide open spaces for rest.

But for green life, it is the time to grow. Amidst the chaos of rent clouds, life bubbles in the muddy earth. Here in the puddling and soaking, in the wet messy as a birthing bed, farmers witness the miracle of metamorphosis. Barley and millet and wheat and sesame flourish, bloom, fruit.

*

Just days before I found out I was pregnant, I read a text that my Nana was dying of stage four cancer all over her bony body. My parents, husband, son, and I visited her the following week, after she’d had a permanent drain surgically installed to ease fluid off her lungs. Nana sat at the edge of her cherry four-poster bed, inhaling oxygen through plastic tubes. She pointed to the door where she’d organized her jewelry in rows of clear little pockets. Do you want any earrings? Please, take them, she said. I’m serious. As we spoke, blood leaked through her incisions.

While my mom gathered gauze and tape to stem the trickles, I suddenly felt wet and slipped into the bathroom. My underwear was stained bright red. I’m having a miscarriage, I thought, but hope whispered, Maybe you’re mistaken. I moved to grab a paper towel from the sink and a shiny red clot the size of an unshelled egg splat on the white linoleum. And that whispering hope closed her mouth.

*

In Ethiopia, flash flooding has punctuated the recent drought. Since mid-March of this year, unusually heavy rains have displaced 240,000 people and killed at least 29. The floods damaged many shelters in IDP camps full of people who had already been seeking refuge from the drought. Donkeys and goats, bridges and schools, seeded fields and homes all washed away in sudden deluge.

*

The next Sunday after my Nana offered me her earrings, after what I thought was the end of the miscarriage, after the blood had slowed to dribbles and just about stopped, I felt the surge of wet again. I rushed to the bathroom. This time, I couldn’t hold back the blood streaming from my body, red lines fingering down my legs. I called out to my husband, I’m hemorrhaging. I bled through my sweatpants to the stretcher the EMTs rolled me out on.

As I lay under a sheet of hospital gown, an ER doctor pressed an ultrasound probe hard against my pelvis. How do you know you miscarried? he asked. I told him my story. Because this, he said, looks like an 8-week old fetus, and on the portable screen he pointed to a little lifeless being crouched in my womb.

*

When I was growing up, the idea of earth being a mother sounded pagan to my church-going ears. And if Mother Earth refers to a pantheistic replacement of God, it still does. But now as a mother myself, I see the name in a different light. Birthed by the One for whom all things exist, the earth births cherries and sea horses and fawns. Nourished by the One in whom all things were created, the earth nourishes all living beings with water and bread. Upheld by the One in whom all things have their being, the earth holds seeds in her wombdark, suckles seedlings, tends cedars and meskel flowers and rue.

Paul himself alluded to this imagery when he wrote that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. Creation is a mother in labor. But what if she bleeds before the hour of birth? What if she miscarries?

*

Miscarriage is a perversion of childbirth. When my husband and I looked at our baby on the ER ultrasound screen, we felt not joy but anguish. (As soon as the doctor left the room, we crouched together in tears.) To a full-term pregnant woman, blood speaks life: the baby is coming, the seed is sprouting. When I labored to birth my son, I bloodsoaked my hospital bed with joy. I bled out the life of my body knowing the great gift ahead. But blood at the wrong time, in an aberrant pattern, speaks death.

The miscarrying mother must still give birth. The obstetrician in the ER, a slender, quiet man who pulled his chair up to my bedside, told me I had three options to birth our dead baby. Surgeons could suction and scrape me out. A pill could force the emptying. Or I could wait.

*

Lately, I’ve wondered how God felt when Jesus died. The Messiah, the Savior of all, the whole hope of the whole world: dead. Did God Himself cry when his only begotten Son bled and suffocated on a cross?

If God grieved the evil of humankind before the Flood, grieved the rebellion of His people in the wilderness, grieved through prophets’ voices–surely He must have grieved the greatest injustice that ever would be: the death of His only Son.

And if Jesus–the very image of God–was deeply moved in spirit and troubled and wept at Lazarus’ tomb, if Jesus was overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death in the Garden of Gethsemane, His sweat becoming like great drops of blood falling to the ground. Does God weep now when he sees his creation, his handiwork, groaning? Does he cry with emptied mothers mourning babies they never held? All creation groans.

*

The worst day of my life was the day that, after some futile waiting, I took the pill that would expel the baby I longed to keep. To prevent nausea, I held the pills in my cheeks instead of swallowing them. Bitter seeped onto my tongue like gall.

Within a half-hour, my womb began to ball into a fist, first with menstrual-like cramps, then with early labor-like contractions. I remembered what the nurse said when I’d been birthing my son, something like Do me a favor honey, and just breathe real long and slow. I beat my palms into the hardwood floor by the bathroom door, keeping rhythm for my breaths. I groaned in those childbirth pains, knowing the end was drought and deluge.

*

On the first Good Friday, rock severed and the earth trembled, shrouding herself in darkness. Along with God and Mary and the daughters of Jerusalem, the earth wept, too, grieving the One who bore her.

Paul writes that all things were created through Jesus, as if the whole of creation had been birthed from his body. Jesus’ life reveals a maternal affection for the earth he made. He chose to be born in the presence of animals. The wind and the seas obeyed him. The lilies were clothed by him, the sparrows fed by him. I wonder if St. Francis illuminated aspects of Jesus’ life the Gospels do not mention: Did Jesus make peace with wolves and preach to birds and bless caught fish? Did the rabbits and sparrows hop into his shadow just to be near Him?

One thing is certain: Jesus said, Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation. While I won’t be evangelizing my vegetable gardens any time soon, I am struck by the all-encompassing nature of Jesus' word choice. Is it too far-fetched to think that even the earth needs to know that one day, in Jesus, she will be redeemed?

*

Though Jesus was a man, I take comfort in knowing that he knew what it was like to bleed. He knew what it was like to feel powerless against the tide of blood. He knew what it was like for life to seep away. He knew what it was like to break in two like thunderclouds rent. The Rock who bore me knew what it was like to bleed in cosmic floods. In the Apocalypse, Jesus wears a blood-dipped robe. There on the hardwood floor, contracting for a baby that would never breathe, I did not bleed alone.

For another month, I continued to leak. The day of my Nana’s funeral, as we clutched umbrellas by her casket in the spring rains, I bled. I waited, groaning, for the day my womb would hold fast like skies emptied of cloud. And one day, the drops stopped.

*

The word for groaning Paul uses in Romans 8 expresses intimate lament: groaning within oneself, groaning in grief, anger, desire. Just once in the Scriptures, this same word is used to describe Jesus.

A man who could not hear and could not speak was brought before him. Escaping the crowd, Jesus took the man aside privately . In the quiet intimacy of his presence, he put his fingers into the man’s broken ears and, after spitting, touched his broken tongue. Matthew writes, Then Jesus looked up to heaven, gave a deep groan, and said to the man, “Ephphatha,” which means, “Open up!” (GNT) And the man was healed.

*

Many Ethiopians believe the end times are near. They point to the wars within and without their borders, the leaking rains, the drought, the floods, the famines. The blood.

The Apocalypse—the story of the end—is a blood-soaked book. A righteous God judges those who spilled the blood of saints and prophets. When God tramples grapes in the winepress of his wrath, the blood rises as high as a horse’s bridle for 168 miles. When the bowls of God’s wrath are poured onto the sea, the rivers, and the springs of water, all turn to blood like the plagued Nile.

Jesus said, All these are but the beginning of the birth pains.

*

When Jesus died, the curtain hiding the Most Holy Place was rent in two like a perineum. In the bloody labor of Jesus, a promise was birthed: one day, a new creation would be born. A new people. Comparing Jesus suffering on the cross to a mother giving birth, Julian of Norwich writes, “He alone bears us for joy and for endless life.” Out of the muck and mess of blood and drought and flood, a green greener than eyes can perceive would flourish. Out of the seeds dead in their casings, the babies dead in their sacs, a life powerful enough to redeem all death would crack open the earth with a shout. These days, this unseen reality is what I’m holding onto.

Until then, we wait for it with patience. Eagerly, groaning, we wait for redeemed bodies and skies that do not break open before their time. Shriveling seedlings and buds, dry stones and rivers wait, groan. And the Spirit prays with groanings too deep for words. God groans with us mothers of flesh, mothers of earth.

Even the groans hold hope. Like timely bleeding, like Jesus’ moan just before a miracle, like apocalyptic blood, they mean the birth is near.

Elise Tegegne

Writer & Author

Elise Tegegne holds an MFA in creative writing from Seattle Pacific University. Her work has appeared in Plough, The Windhover, Dappled Things, Fathom, and The Indianapolis Star, among others. Her first book In Praise of Houseflies: Meditations on the Gifts in Everyday Quandaries (Calla Press) will appear in 2025. She lives with her husband and son in Indianapolis.

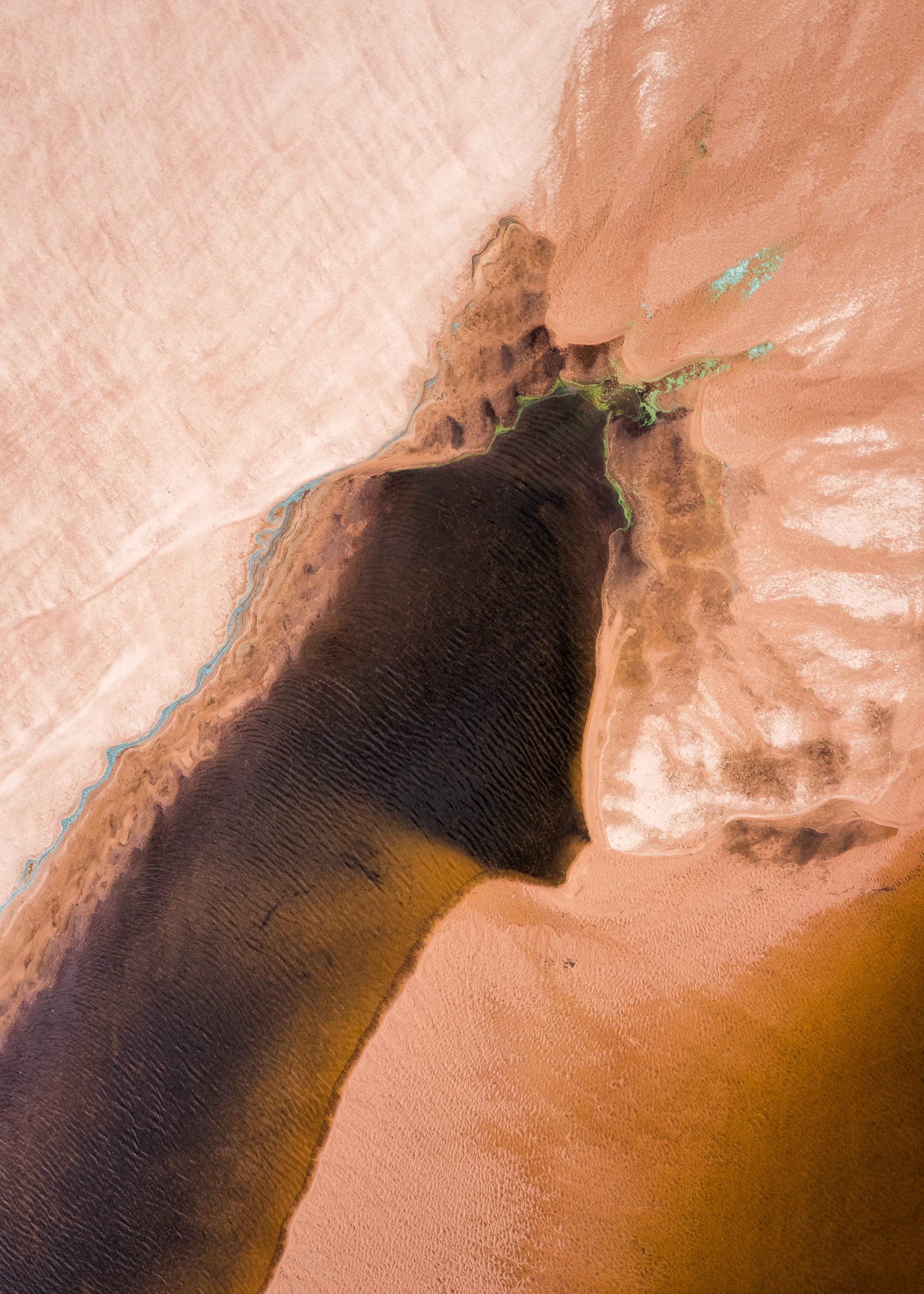

Photography by Dave Hoefler