All Mysteries and All Knowledge

All Mysteries and All Knowledge

Christina Gonzalez Ho

On the Half-Learned Language of Prophecy

Two days after Christmas, my husband, Christian, emails me a list of prophetic words he received in 2015. “This is interesting and encouraging,” he writes. “I just came across it while cleaning up my files.” The email contains words about our marriage (we weren’t yet engaged at the time), our future ministry and children, and his academic career. I am sprawled on the couch in the next room, laptop open. When I see the email I skim it quickly, then close out the window, a little weary.

“Did you get my email?” he calls from the guest room.

I make a noncommittal sound, which he can’t hear from behind the door. He FaceTimes me.

“Hey, did you read my email?”

“Mmhmm,” I say, gazing somewhere offscreen.

“So, what did you think?”

“Interesting.”

“That’s it?”

I hesitate again. “I guess I just don’t know what to think of words like this anymore. They’re so grandiose.” I open his email again and begin reading it out loud. “‘Something is about to shift…you are going to move forward so fast, it will be like a light bulb coming on’? Would you say that actually happened?”

“Yeah, I think so,” he says.

I raise my eyebrows, intrigued. “Really? In what way?”

“When I took those studio classes during my third year, I suddenly understood why I was studying architecture. That was definitely like a light bulb coming on. And that’s the year I started working with the people I’d eventually do my thesis with.”

“Hm.” I consider this for a moment. I’m not convinced, but I don’t want to be a downer. “Sure, I guess that’s encouraging. But when you got this word, is that what you thought it meant? Didn’t you think it meant you’d suddenly become rich and famous?”

He laughs. “Probably.”

“And you’re not disappointed it turned out to be so much more…subtle?”

“No. I’m okay interpreting things expansively. I’m not like you.”

*

Me: after nearly twenty years in charismatic Christian circles, still struggling to wrap my head around prophecy. In the Scriptures, they all seem so literal: Elijah’s three-year drought, Mary’s virgin pregnancy, Ananias’s GPS-precise directions to Paul. Modern-day charismatics with prophetic ministries play up their stories of literal words, too, calling out phone numbers and birthdates from stages. These are the stories I’ve always found aspirational. Why even have prophecy unless it tells you something you couldn’t have known otherwise, something true? And how better to tell if a thing is true than to see if it happens—literally? I found it annoying, a cop-out, when people responded to prophetic words that failed to materialize with, “Well, maybe God meant it in a different way.”

Like at the end of 2015, when I asked God to give me and Christian the same one-word theme for the coming year as a sign that we were meant to be together. Earlier in the day, I’d prayed and heard the word “prosperity.” Without telling Christian my own word, I asked him to pray and ask God for his. A few moments later, he turned to me a little sheepishly.

“I got a word, but I probably made it up. It’s ‘prosperity.’”

I was thrilled. For the rest of the year, I kept waiting for us to become prosperous. I had taken a $100,000 pay cut to become a law clerk in Boston while Christian finished school, so there was no way we could become rich “in the natural” (as the charismatics say) that year—but why else would God give us both the same word? Plus, I’d never gotten a money-related word before. Surely something supernatural was afoot.

Eleven months passed with no influx of cash. But then, at the very end of the year, a mutual friend introduced us to a wealthy philanthropist couple, who took an immediate liking to us. “Let’s stay in touch!” they insisted, at the end of our second three-hour dinner with them that week. It was too uncanny to be unrelated to the word. At last, it seemed, God was bringing us into our prophetic promise of prosperity.

By spring of the following year, though, none of our prospects had changed. The philanthopists talked enthusiastically of hiring us for a special project, but the project kept failing to materialize, and their response-times between emails had gotten longer and longer. While complaining about the situation to my friend Ben, I mentioned the word about prosperity, how it seemed to be falling through.

“Maybe God meant a different kind of prosperity,” he offered reasonably. “Prosperity can mean a lot of things, can’t it?”

Responses like that irritated me because they seemed weak. They let God off the hook, free to keep tantalizing people with grand prophetic hints, but only fulfilling them obliquely, or not at all. If God knew I’d interpret “prosperity” literally, why not use a different word? Better yet, why not simply deliver?

There’s precedent for my insistence on prophetic fulfillment—not just Biblical events, but ones from my own life. In college, when my beloved maroon Schwinn was stolen, a friend of mine emailed me saying he’d heard God say I would find my bike in nine months. Nine months later, on my way to Afghan Literature, I glanced at a stand of bikes and saw to my utter disbelief my Schwinn, unlocked, still festooned with the stickers I’d placed on it freshman year.

Another time, while volunteering at an exchange program for Japanese college students, I felt God say one of them would become a Christian by the end of the summer. The program was secular, and aside from sharing that I was a Christian, I didn’t have the opportunity or confidence to proselytize—but sure enough, in the program’s final week, a student approached me and asked me to pray with her to receive salvation.

There have been less dramatic fulfillments as well: the prophecy I got about becoming a worship leader, from a pastor who’d never met me before and didn’t know I was a musician; the promise I felt God make to me when I was 18 years old that I would travel the world, which has since proven true. These are the kinds of stories I tell to friends of mine who are bemused by my faith. I don’t try convincing them that Christianity is more reasonable or logical than any other belief system; I simply tell them stories that insist on being reckoned with, stories that speak for themselves. To me, they are proof that the things I learned about God from the Bible, my parents, and pastors are true: that God is real, that he is involved in my life, that he cares. The downside of this way of thinking, of course, is that when the prophecies are not fulfilled, all of these things are called into question.

The worst disappointment, the one that hurt the most and still aches sometimes like an old scar, occurred in college with my friend Ana. We were standing outside my dorm room chatting when she’d broken down in tears. Her father was dying of cancer. He’d had it for years, but recently, the doctor had given him just a few more months to live.

I was new to hearing God’s voice and praying for the sick, and too shy to pray directly for healing right then and there. But back in my room, I knelt on the floor and prayed. “God, if you want to heal this man, please tell me his name so that I can pray for him directly.” Then I sat quietly—waiting, listening. In my mind’s eye, a cloud of letters began to form. I focused harder, trying to discern them. P…E…T…J…R…S…Peter? I pulled out my phone and texted my friend. “What’s your Dad’s name? I’d like to pray for him.” She texted back: Petrejsk.

The next two weeks were a blur of tears and joy. Ana was eager to learn more about this God who was so kind and loving that he would heal her father of cancer. Together, we drove an hour to Petrejsk’s house to pray for him. “God loves you,” I told him as I knelt beside his bed. “He knows your name. He wants to heal you.” A week later, Ana texted me excitedly. Petresjk’s white blood cell count was going up and the doctor couldn’t explain why. I emailed all of my friends from my high school youth group and even shared the story at my campus fellowship meeting. For many of them, it was the first real miracle they’d seen.

Then, things fell apart with dizzying speed. The week before Thanksgiving, Ana texted me that Petrejsk’s cancer had taken a turn for the worse. Two days later, she called me from the hospital. Petrejsk was on his deathbed. Did I have any Psalms of comfort and peace she could read? “But remember,” I said, practically pleading, “God said he would heal your dad.” He died later that night.

All winter long, I grieved and raged against God, mostly alone. My Christian friends, who’d been so excited to hear my stories of receiving Petrejsk’s name in prayer and of the ensuing white blood cell increase, either shrugged sympathetically—too confused themselves to offer words of relief—or else suggested God had meant to heal Petrejsk spiritually, by saving his soul. I wasn’t swayed. If Petresjk had converted to Christianity, then perhaps—but when we’d driven to his house and told him Jesus loved him, he’d only said, “Yes, I believe in God. Whoever he or she may be.”

After he died, I saw Ana less and less often. We didn’t have much more to talk about, and I felt guilty, as if I’d lied to her. But really, it seemed as though it was God who’d lied to both of us. It took me a long time to get over that idea: that God had betrayed me. In the end, I didn’t resolve my anger so much as grow exhausted of it. It was such a heavy burden, to stay angry at the one I’d ordered my entire life around. Why God had spoken so clearly, only to fall into utter silence at the pivotal moment, I gave up trying to figure out. But for a long time, I resented the fact that I’d had to give it up.

Eventually, the job with the philanthropists came through. They created a special project for us, with a yearlong contract in Los Angeles, and paid us well. For the next year, Christian and I were financially prosperous—but it’s only in writing this now that I’m seeing it that way. At the time, I was focused on other things: doing the job well, securing the next opportunity. I never looked around and thought, “At last. Prosperity!” Perhaps there are other words whose fulfillment I’ve missed because I’ve forgotten about them. Perhaps it’s unfair of me to be so exacting about some prophecies and forgetful about others. Then again, at the time I imagined “prosperity” to be grander and more permanent than what we actually experienced: a year of abundance, followed by three years of scarcity. So was the word fulfilled after all? Is it unfair to say it wasn’t, or would I be letting God off the hook if I said it was?

*

“Dreams are messages from the deep.” So begins Denis Villeneuve’s film adaptation of Dune, in which the protagonist Paul Atreides wrestles with his burgeoning psychic abilities. Paul’s visions are cryptic and initially sparse: a woman’s face, a lock of hair blowing in the wind, a flash of sand. In one vision, the woman beckons Paul lovingly into a canyon, her facial expression now tender, now threatening. In another, she kisses him, then stabs him—he watches himself bleed out. This dream recurs several times, but its meaning remains unclear.

When Paul’s father is murdered, he is forced to flee into the desert. Caught in a deadly sandstorm, Paul slips into a vision of a man with kind eyes. “Follow the friend,” a disembodied voice tells Paul. In flashes of dialogue that seem to come from the future, the man guides Paul safely through the sandstorm and he is saved. “I will show you the ways of the desert,” the man says to Paul. “Come with me.”

Paul’s visions are no mere fantasy—he sees his beloved teacher die in battle months before it happens in real life. He also perceives that his mother is pregnant before she herself is aware. But his recurring vision—of the woman, the stabbing and dying—unfolds much more uncannily. When Paul meets the man from his sandstorm vision in real life, he turns out to be an enemy. The man challenges Paul to mortal combat, and it is Paul who stabs the man and watches him die. As the victor, Paul is adopted into the man’s tribe—thereby securing his only chance of survival in the desert.

The death in Paul’s visions is Paul’s own, and it isn’t: by killing the man, Paul kills the version of himself that has never taken a life before. The man is his mentor, despite being his enemy—for it is through his death that the tribe accepts Paul into its fold, his people who will show Paul the way of the desert. Dreams are messages from the deep. Unlike dispatches from the surface world, which tend toward clarity, Paul’s visions are murky; they communicate in a language he has not yet learned to speak.

Surely the historical understanding of prophecy hews closer to this description than the one I grew up with: that words from God come “from above”; that they are crystalline and lucid. The “greatest hits” of Biblical prophecy—from Elijah’s drought prediction to Gabriel’s announcements to Elizabeth and Mary—feature immediate, clear-cut fulfillments. But the rest of them bear a closer resemblance to Paul Atreides’ dreams. The books of the major prophets are full of visions, more poetry than reportage, that speak of judgment and redemption in the same breath—events whose fulfillments take place generations apart. To force them to adhere to conventional rules of space and time would be to render them unintelligible. Jesus’s own declaration that he was the Messiah, the descendant of David who would become King, seemed patently untrue when he was crucified and buried. It was true, and literally so—more than his disciples could have imagined. But the message came to them from the deep, out of the darkness and the whirlwind, and they had not yet begun to discern it.

*

In the three years after our year of prosperity, my husband and I journeyed through career-death, financial lack, and cancer: hard, crushing lessons in surrender. I emerged from that time weaker, perhaps more prone to letting God off the hook, if only because I’d seen so thoroughly and repeatedly how small I am. How ludicrous it is to try and exert control, whether over knowledge or circumstances—at least, in the ways I’d tried before. Then, too, I’ve begun to consider that perhaps prophecy is a language I’ve only ever half-learned. An ancient tongue, with its own inflections, connotations, and syntaxes, of which I know nothing—grammatical rules to whose logic I must acquiesce, not the other way around.

In those three years, we received many prophetic words that have not come true—words about good health, children, success, recognition. The weight of those words carried us through that time; inscrutable as they are, they carry us still. Instead of attempting to break them open, I am trying to let them open me: to reach their long, dark tendrils into my ribs and squeeze until I crack open, wide enough to really hear, really see.

Christina Gonzalez Ho

Author & Writer

Christina is the author of the audio series The Last Two Years and coauthor of Los Angeles: Mestizo Archipelago (Pinatubo Press). Her work has appeared in Image Journal and Between Lands Magazine. She holds a B.A. from Stanford University and a J.D. from Harvard Law School.

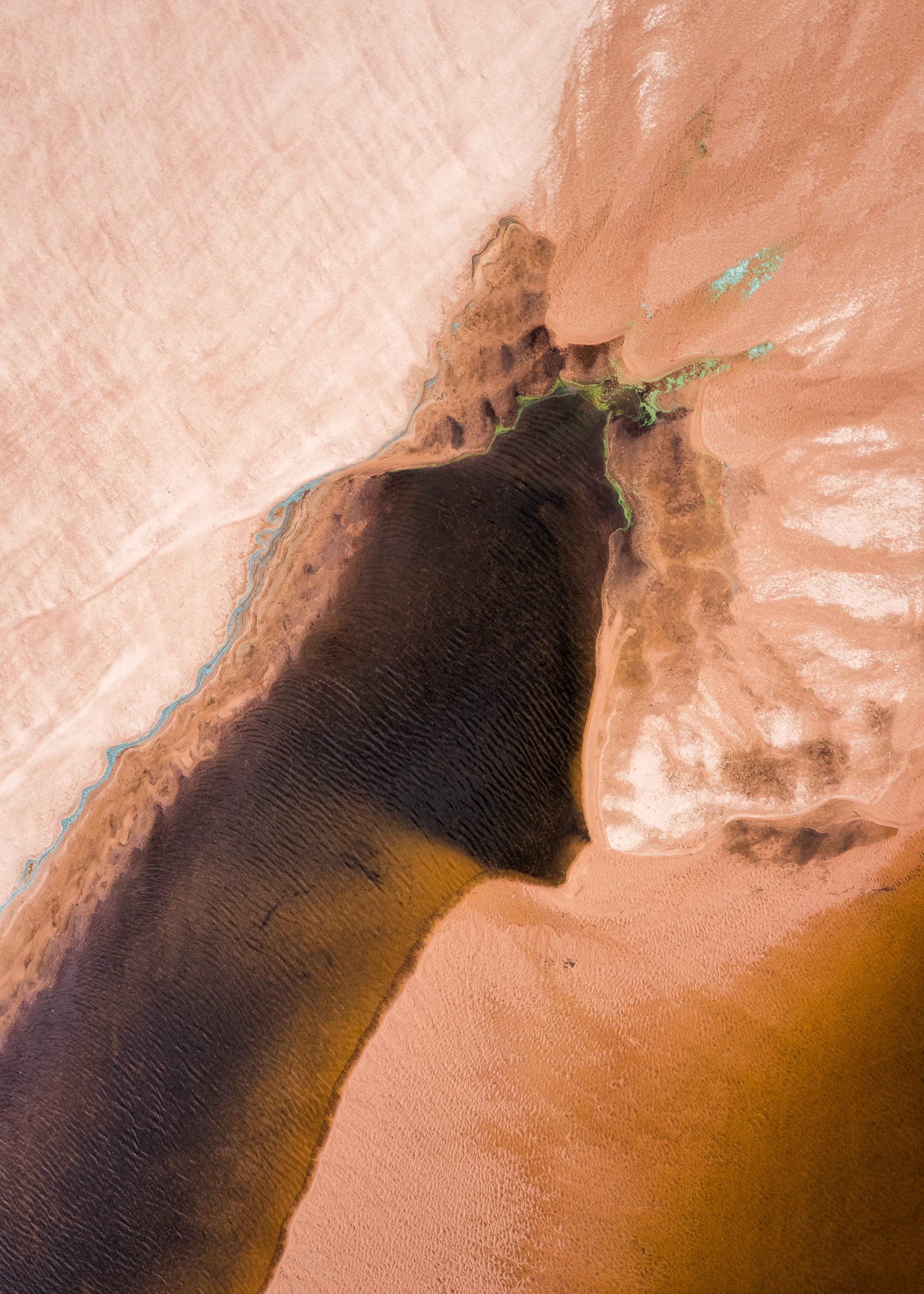

Photography by Allec Gomes