The Oxygen of Grief

The Oxygen of Grief

Ryan Ramsey

I remember the day when the small college I attended lost a fellow student suddenly and tragically. It was the year after I graduated and I worked in the Residence Life department. The student who died, Ben, was beloved in the community. He was a missionary kid—friendly to everyone and also a very good soccer player. The school held a memorial service for him in the chapel and his parents flew in from Africa to be there. The service was beautiful and the collective grief that filled the auditorium that evening rose up like a burnt offering. To this day, I hold the poignant memory close, remembering the way it was possible, and even encouraged, to grieve in community during that memorial—one of the few occasions where we are given societal permission to express our loss.

I remember witnessing the physical and spiritual complexion of the community shift that night. So did mine. Gathering together in the presence of loss stripped us of our pretenses, at least for the few hours we were together in the dim auditorium. The liturgy, along with the towering stained glass of the chapel, provided us a safe container to hold our grief—and be held by one another. As we gathered outside afterward, I hugged and embraced dozens of people with shared tears. Many of us met one another’s gaze through the unfiltered lens of grief for the first time. There was no shame. I wept intensely for several hours alongside other students after the service. Nothing about it felt taboo. Everything about it felt uniquely alive. It was love manifesting deeply and tangibly among us as we released the pain of an unexpected loss.

A memorial or vigil service is an accepted setting to express our sorrows when someone we loves passes away. But the reality is, loss registers in our bodies every day in countless forms, and what happens when we do not have a ‘permitted’ place to welcome it or hold space for sorrow with a community? When was the last time you attended a grief ritual for a lost job or marriage?

*

In The Wild Edge of Sorrow: Rituals of Renewal and the Sacred Work of Grief, author and therapist Francis Weller says, “we live… in a grief-phobic and death-denying society. Consequently, grief and death have been relegated to what psychologist Carl Jung called the shadow.” What is given to us as a sacred gift has been exiled and privatized in our culture, a reality too easily mirrored in the church. Paul was concerned to remind the Thessalonian church that they do not grieve “like the rest, who have no hope” (1 Thess. 4:13). Weller is concerned that in the numbing and breakneck pace of modern society, grief becomes the nemesis we seek to cast out entirely. When we live this way, we engage in friendly fire with grief—the energy that is given to accompany us as a holy ally. Weller continues, “Sorrow is a sustained note in the song of being alive. To be human is to know loss in its many forms. This should not be seen as a depressing truth. Acknowledging this reality enables us to find our way into the grace that lies hidden in sorrow. We are most alive at the threshold between loss and revelation; every loss ultimately opens the way for a new encounter.”

Because it permeates our world in seen and unseen ways, grief will always ‘move in’ to our hearts and homes as a regular guest. But it also desires the attention, space, and freedom to move out. How grief manifests in our bodies depends on how we greet it. Sorrow lives best as a tenant we welcome with hospitality, share sacramentally in the company of others, and honor with gratitude until the “lease” is up. But as an unwelcome and hidden dweller, the layers of losses we inhabit slowly sabotage us of the gift of life.

Jesus, the “man of sorrows, acquainted with deepest grief” (Is. 53:3), moved and mourned among us even as he proclaimed the beauty of God’s kingdom. He dwelt among the ashes and accents of grief that meet us daily like the oxygen that enters our lungs. But, “we turned our backs on him and looked the other way.” (Is. 53:3) We hid our faces from him like we are prone to hide from the face of grief.

Weller says when we decline the invitations of grief to honor our losses in unhurried spaces of remembrance and ritual, it inevitably expresses itself in more painful (and sometimes debilitating) ways. When we do not protest a culture that promotes the “skill” of rejecting the oxygen of sorrow with all manner of distraction, we choose to stop breathing. Much of our reorientation to grief requires unlearning. It’s not that we must desire grief as some twisted pleasure; it’s that if we desire to participate fully in our lives, we must grieve. “This underworld domain is the sanctuary of our initiatory ordeal in which we are reshaped and remade under the hands of grief. It is the place where our apprenticeship with sorrow and our ability to be truly alive is deepened. It is the dreamtime offering images that quicken our souls and cause us to catch our breath.”

You can probably name more than one loss you are presently living with that has not been duly honored. What would it look like to hold space for the loss in community? Who would you invite to come and bear witness?

When we bear witness to grief as active participants of our union with Christ, we protest the darkness of this world. We lay ourselves bare in the light of hope. We groan with all creation so that we don’t lose our enchantment as creatures who still practice wonder beneath God’s canopy.

*

I sometimes feel that accessing unnamed and unattended layers of grief in my own story is akin to solving a Rubik’s cube. Beauty often helps break loose my sorrows into accessible parts that can be touched, held with gentle reverence, and released.

My wife and I decided to take an impromptu day drive to the mountains a few years ago as fall arrived. It was a heavy and hard season. As we weaved upward toward the mountain pass through hairpin turns, we were arrested by the stunning colors of aspen trees surrounding us on all sides. The vistas overwhelmed me with hospitality toward significant pain I was holding. The burning glow of the aspens stood like a burnt offering to my grief. The beauty all around me invited the tears of sorrow to rise up in me safely and freely. No one in my life had died but I released a lot of grief that day in the company of cool, autumn air and vibrant groves.

Sometimes God provides us unplanned ritual space—like a day drive—to honor our sorrows. We all need moments, days, and seasons for sacred release. There have been times when my sorrows surfaced like a broken dam and the tears overwhelmed me. But there have also been days like the drive through Colorado aspens—when grief arrived in my eyelids like a quiet, gentle breath of consecrated air in my lungs. It was like God knew the excess weight of sorrow inside me needed to be held. The silent beauty of trees became a great cloud of witnesses.

Ryan Ramsey

Pastor & Writer

Ryan explores the intersection of spiritual formation & pastoral integrity and has been published in Fathom Magazine

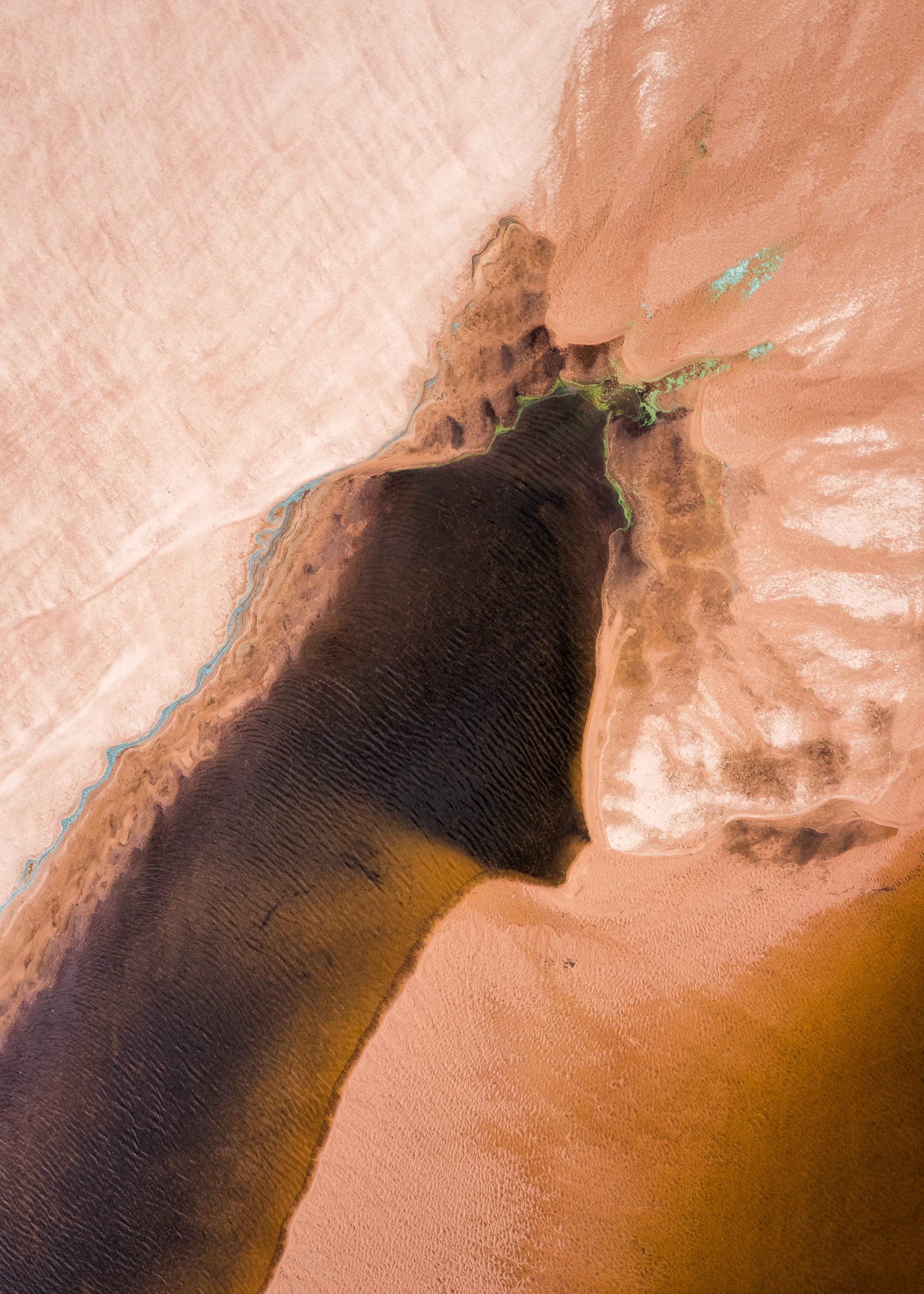

Photography by Ralph Kayden