Writing in the Rabbit Room

Writing in the Rabbit Room

On the Prayerful Experience of Writing Every Moment Holy

An Interview with Douglas Kaine McKelvey by Liz McEwan

“Children of the Living God,

“Let us now speak of dying,

and let us speak without fear,

for we have already died with Christ,

and our lives are not our own…”— “An Exhortation Making Space To Speak of Dying,” Every Moment Holy, V. II

I found my favorite Douglas McKelvey book by accident.

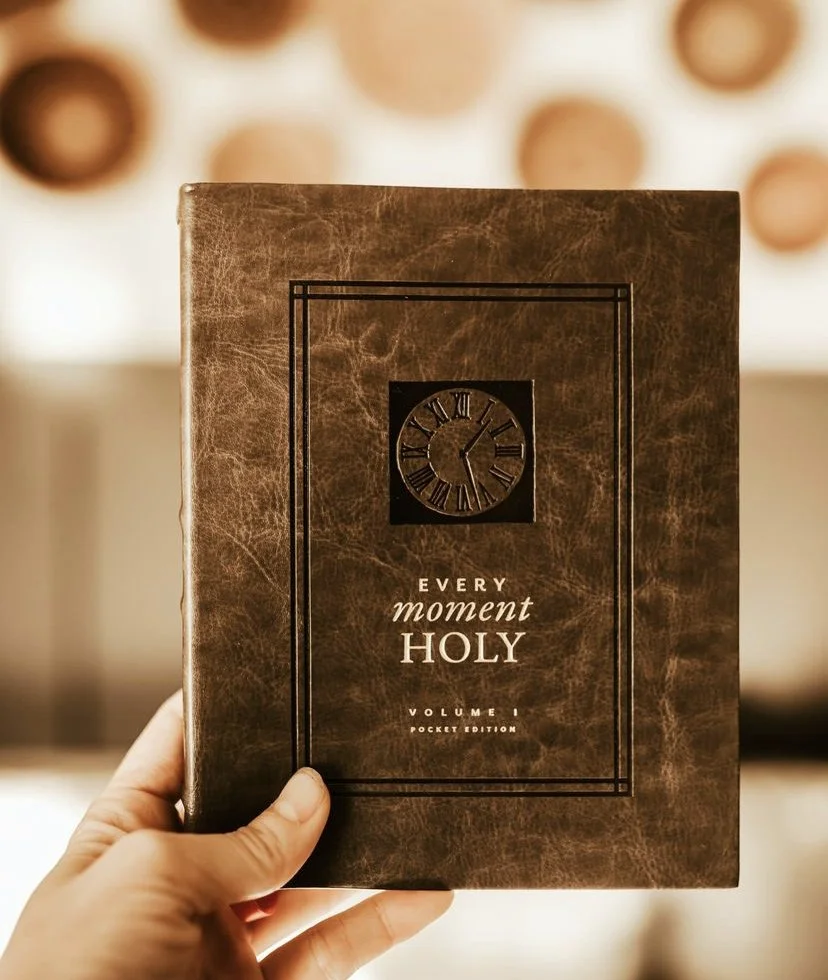

Wandering around the expo at a large homeschool conference, I stopped at the Rabbit Room booth to shop for myself and my kids. Having never been disappointed by anything released by Rabbit Room Press, I employed the old “judging a book by its cover” trick and, drawn to the cover illustration by Zach Franzen, I picked up a short novel called The Angel Knew Papa and the Dog.

I didn’t recognize the “Douglas Kaine McKelvey” on the cover as the same Douglas Kaine McKelvey who had written Every Moment Holy, a book of prayers and liturgical readings that was currently making its rounds among my friends. It wasn’t until I Googled the author’s name, hoping to find more of his work, that I made the connection.

Lucky for me, I already had a copy of his newest book.

*

For those raised outside of a liturgical worship tradition, scripted prayers and readings can feel strange at first. But McKelvey believes there’s something deeper to discover underneath the rhythms and poetic language of liturgy.

“I grew up in a church where we would have been very suspicious of liturgy,” he explains. His first exposure to liturgy was limited, but it was a profound experience.

Though he was a Believer, when he was in college, he struggled to understand the basic tenants of his faith. He felt that the expressions he’d been given “lacked a coherent theological framework.”

A friend invited him to a church where they used the Book of Common Prayer in worship and, as he recalls, “something resonated deeply with me.”

“I felt like I didn’t have to be on my guard. This was something that was rooted and had stood the test of time.”

“In these liturgical prayers,” he explains, “there was an affirmation of those things as well. The beauty of it mattered. It was a part of the offering. The truth is being incarnate in the words—the skin—of the language.”

As a writer, words were important to Douglas McKelvey. Particular words and phrases of the liturgy he’d heard stuck with him and had “a tutoring, discipling effect.”

Later, in his regular writing practice, McKelvey played around with prayers and poetry in liturgical form (By this time, he was regularly attending a liturgical church.) He appreciated the way the limitations of a sonnet, for example, could inspire creativity.

He didn’t intend to write a liturgical book. What became Every Moment Holy began simply, as a prayer.

*

It seems ironic that a liturgical book would be published in Nashville, Tennessee, a town known as the Gospel capital of the world and a center of Evangelical publishing and contemporary Christian music.

It seems ironic, that is, until you get a peek at the side of Nashville beyond the frenetic glow of Broadway.

See, first, Art House, a nonprofit founded by Andi Ashworth and Charlie Peacock (Ashworth) to cultivate and disciple the creative community around Nashville.

Douglas McKelvey moved to Nashville in 1991 on an invitation to help launch the project, which has since expanded to become Art House America and has birthed two other Art House locations in St. Paul, Minnesota and Dallas, Texas.

Rabbit Room is another place to explore—though “place” is a bit of a misnomer. Rabbit Room is a passion project of writer and musician Andrew Peterson and, seemingly, an evolution of (circa 2006) The Square Peg Alliance.

Though centered around Peterson’s own home, dubbed North Wind Manor, Rabbit Room programming includes podcasts, a music and bookstore, a publishing house, a yearly conference, and a local concert series.

Unlike some more commercial publishing enterprises, Rabbit Room engages artists and fans in a community atmosphere, blurring the lines between creator and patron and fostering connections within the creative community.

For Christian artists around Nashville—and especially those who don’t feel at home in the commercial music scene—these places have become like community centers where professional relationships flow over into rich, personal ones. In addition to working together, they share in ordinary things like raising families, indulging side projects, laboring over unfinished works, and navigating their personal faith. This is where unique literary projects like Every Moment Holy come to life in Music City.

*

About 5 or 6 years ago, McKelvey was working on a novel, but he felt undisciplined and frustrated. He remembers, “I needed a prayer that I could pray that would focus me, reorient my mind in relation to my creator, to my stewardship of my craft… and in relation to the people I hope to serve by what I’m trying to create here.” He wrote a prayer for, specifically, the act of writing fiction.

The prayer evolved into a liturgy, with parts for a leader and for people to respond. After completing it, he thought it might be worth sharing at the upcoming Hutchmoot festival, as a kind of benediction during a session for writers. People loved it.

“It was in that moment that the entire vision unfolded,” he says.

Maybe this wasn’t just a novelty, he thought. Maybe prayers like this could serve the church, helping shape people’s trust in God’s sovereignty over every moment.

He wondered what it would look like to “unpack” some big questions about the role of everyday life—things like preparing a meal, changing a diaper, and keeping bees—in the Kingdom of God.

Theoretically, he says, we pay “lip service” to this concept. What if he could provide a tangible tool to help people develop these rhythms of spiritual discipline and focus in their daily lives?

The first volume of Every Moment Holy was released in 2017.

It includes over 100 new prayers and liturgies on a broad spectrum of topics, both playful and serious, including many commonplace scenarios like gathering around a bonfire or reading a favorite book. Some are written as personal prayers; others are meant to be read in a group.

*

After publishing the first volume of Every Moment Holy, McKelvey says he “crossed the finish line with nothing left.” But he knew he’d left something important out. As he looked ahead at yet another daunting creative project, McKelvey’s collaborative community was instrumental to writing the second volume of his book.

“The first volume felt pretty extensive,” he explains. “I thought maybe people would get everything they needed. But the gaping hole in it was that there was no prayer for people in the immediate aftermath of losing a loved one.”

He knew it had to be written, but he couldn’t dive into it just yet. He needed a break. A year later, when he was finally ready, he began writing “a liturgy for those who grieve.” And, within a week or so, it was ten pages long.

“I didn’t know it would be a full volume,” he says. “I was chasing the idea. And, then, once I knew it was a book, I didn’t feel like I was qualified to write it. I knew I was going to need community involved.”

McKelvey engaged in a year-long process of exploration, talking with people who had walked through the experience of grief and loss.

“They were willing to open up their own wounds, to go deeply into that kind of loss… In doing that, they were serving those who would follow them in that same journey.”

These new friends helped him vet his expressions as he wrote, giving feedback, correcting his assumptions about their experiences. Every conversation led to additional prayers as he better understood how to serve people in their moment of loss.

He wrote prayers for those who’ve been widowed. He wrote prayers for those who’ve lost someone to suicide. He wrote prayers for those who serve those who grieve. He wrote prayers to be prayed by those approaching their own death. “What does it look like to follow our Shepherd into that?” he asked.

*

In 2021, Rabbit Room Press released McKelvey’s second volume of Every Moment Holy. It is markedly more severe than the first and, plainly, subtitled “Death, Grief, and Hope.”

The themes of wonder, redemption, and the journey through suffering are common in McKelvey’s writing. But how is he so comfortable exploring these darker experiences of the Christian faith? He recalls a transformative moment:

It was the beginning of autumn. He was driving home from church, taking a scenic route. The leaves were changing colors and the trees before him formed a cathedral arch. He was listening to the song “The Stolen Child” by The Waterboys. The song is a setting of the W.B. Yeats poem by the same name which is, itself, a retelling of an Irish fairytale of a magical land where fairies live to escape the suffering of the world.

“Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world's more full of weeping than you can understand.”

The wind blew. The leaves fell before him. And the synthesis of the moment—the colors, the leaves, the poem—opened up something in him. It was a hunger and yearning for what lies beyond the suffering and grief of being human, for a world of bliss and beauty.

It was a pivotal moment for his faith, rooting him in the hope of redemption.

“If Christ is who scripture says He is,” he explains, “then He must be the fulfillment of all this that I’m feeling… But that’s not the Jesus I was taught. No one has ever tied Him to these yearnings.“

It’s the deep hunger to know Jesus—in the midst of suffering and grief—that drives McKelvey’s writing. He says he’s always putting himself in the story, “sifting through what I believe and the chaos of my emotions and asking, ‘Where’s the solid ground?’”

“When I write,” he says, “I’m frequently drawn to this place of the story, even with non-fiction writing, where it’s a personal proving ground for what I believe or the validity of what I believe.”

“I’m going to dive down into this muck and see if there actually is firm footing somewhere underneath it,” he says. “If these things are true, then they have to be true in the midst of the worst things we experience.”

Liz McEwan

Writer & Journalist

Liz is a proud Cincinnati resident, wife, and mamma. She is a local freelance journalist and social commentator. You can find her blog at ejmcewan.com

Find Douglas McKelvey’s work here