Views from Fidelity

Views From Fidelity

Cole Hartin

My wife and I met on an airplane from Toronto to Vancouver when we were starting out as freshmen at college. We were just barely post-pubescent, both wearing v-necks and straightening our hair. We spent a few months getting to know each other, then, half a year dating, half a year engaged, and we were married within two years of having first met. It’s odd, but I remember the dusty floral suitcase I carried the first time I saw her.

I grew up in a Christian tradition that downplayed the importance of romance, and, as a true fundamentalist, I took this to the extreme. I saw romance, and sexual attraction, for that matter, as a kind of necessary evil that grew up along the platonic ideal of married life. I was surprised by the butterflies, by the overthinking, the dissipation of hunger. And I didn’t like it.

Amy said I won her heart, when, on some desperate attempt to get her attention, I purchased her favourite cereal, and, asking her to let down a rope from her dorm room window, I attached the box to the bottom and had her pull it up. The family-sized box of frosted Mini-Wheats did the trick.

Our relationship had the touches of euphoria that accompany all twenty-something lovers. The fast-beating heart when hands brush, the time-wasting walks, discovering the beauty of sunsets and the accompanying excuse to be alone.

And yet for all of this, I was anticipating the ebbing of romantic feeling, stoically set for the drop in oxytocin. I had taken the words of theologian Stanley Hauerwas to heart when he explained, “A Christian marriage isn’t about whether you’re in love. Christian marriage is giving you the practice of fidelity over a lifetime in which you can look back upon the marriage and call it love. It is a hard discipline over many years.”

What Hauerwas is getting at here, I think, is that the ephemeral giddiness of infatuation lacks the solidity on which to build a foundation that will last. As a Christian, and as a priest, the constancy of marriage over months and years matters deeply.

To be frank, I know and have seen long-lasting marriages that devolve into dull, joyless monogamy. This is one of the risks of fidelity. But, being carried away by the electricity of love has its own risks. Divorce, separation, and the financial implications of both. These are difficulties that can be avoided. If you throw children into the mix, a relationship falling to pieces is a whole other level of misery.

Having a stable marriage matters, not only because of its practical perks—like emotional intimacy and tax benefits—but because marriage, in the Christian tradition, is a living sacrament of the love of Christ for his Church.

*

Before I was a priest, I was a barista at Starbucks. I was in my early twenties, and one of the only people on staff to be married. I took a slight pleasure at the surprise featured on my colleagues’ faces when they found out my partner was actually my wife.

“But you're so young to be married!” they would exclaim.

“Yeah, I got married really young. We were only fourteen,” I would respond to their awkward stares as they tried to conceal their embarrassment.

“I’m kidding,” I’d finally say, “but we did get married when we were twenty.” I learned that starting with a shock would make our real ages seem less unusual.

Conversations like these would almost inevitably turn to my faith, because, in the twenty-first century, why else would anyone get married while they were in college? An unexpected pregnancy, maybe? Or as an act of rebellion for downwardly mobile youth?

Early marriage smacks of right-wing fundamentalism, and probably for good reason. There was a touch of fundamentalism in the charismatic Christianity of my youth. By the time we were married, we’d left the fundamentalism behind, but maintained the best of our Christian heritage.

Even though most people I worked with at Starbucks did not share my beliefs, they gobbled up the story of my life. Many of them were queer and marriage qua marriage was still politically fraught. My marital life interested them, I think, like an exotic specimen from ages past might interest them.

One evening, as the manager and I closed up the cafe and counted the coffee beans, I could sense the curiosity overtake my boss.

“So how did you know that Amy was the one?” she asked me.

“I don’t know,” I replied, “I don’t even know if we all have a ‘one’”.

“So you don’t think she’s your soulmate?” she asked in return.

“No, it’s not that. She is, but it’s not because of fate, or anything like that, but because we both committed to love each other through thick and thin,” I explained.

She looked at me, and her eyes turned glassy for a moment before she turned away to wipe the counter. “Hmm,” she murmured.

“Marriage isn’t really about how you feel,” I went on, “not really, anyways. It’s about the commitment you make to love one another.”

This kind of sentiment seemed natural to me, but to many of my colleagues, I think it appeared old-fashioned and romantic, if entirely useless. Like I said, I always believe that marriage was more a matter of the will than the heart, and if the heart came along that was a bonus.

*

In Genesis, we see the marriage of Adam and Eve, then the proscription of marriage outside of Israel shows up in Exodus. The detailed case-law about the boundaries of marriage takes up ink in Leviticus as does marriage-as-salvation in Ruth. We must not forget the love-sick poetry of Song of Songs, nor Hosea’s marriage to Gomer that becomes a symbol for Israel’s relationship with God. Jesus teaches about marriage and divorce in the New Testament too, but St. Paul gives the most detailed instruction. Celibacy is the ideal, he says, “but because of cases of sexual immorality, each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband” (1 Cor. 7).

St. John Chrysostom, a few centuries later, thought a lot about this instruction. He even wrote a homily about how to choose a wife. St. John is writing in a time far away from ours, with quite different cultural norms. Husbands were the ones to choose their wives, it seems.

His advice is to listen to St. Paul. Beyond that, he suggests prospective husbands be cautious, be careful, because as he tells them, “If you take a bad wife, you must endure the annoyance. If you are not willing to do this, you incur the guilt of adultery by divorcing her.” Moreover, St. John thinks men looking to be married should aim for one thing: “Let us seek just one thing in a wife” he says, “virtue of soul and nobility of character, so that we may enjoy tranquility, so that we may luxuriate in harmony and lasting love.”

Not the most romantic, certainly, but very practical. I hadn’t read St. John before I was married, but I followed his advice, more or less. Amy is a virtuous soul, of noble character. But she is also beautiful.

*

For most of my ten-year-long marriage, the notion of having this kind of marriage-as-covenant has proven successful. I believe now more than ever that the Christian sense of marriage as a sacred covenant, where it is necessary to make some kind of vow to love one another before God—it can work. It has the most staying power, and I think our common life stands out because of this. Hauerwas is right, then, that marriage is the practice of fidelity over a lifetime. But I also believe he didn’t have the full picture; being in love does matter, even if it’s not the central thing.

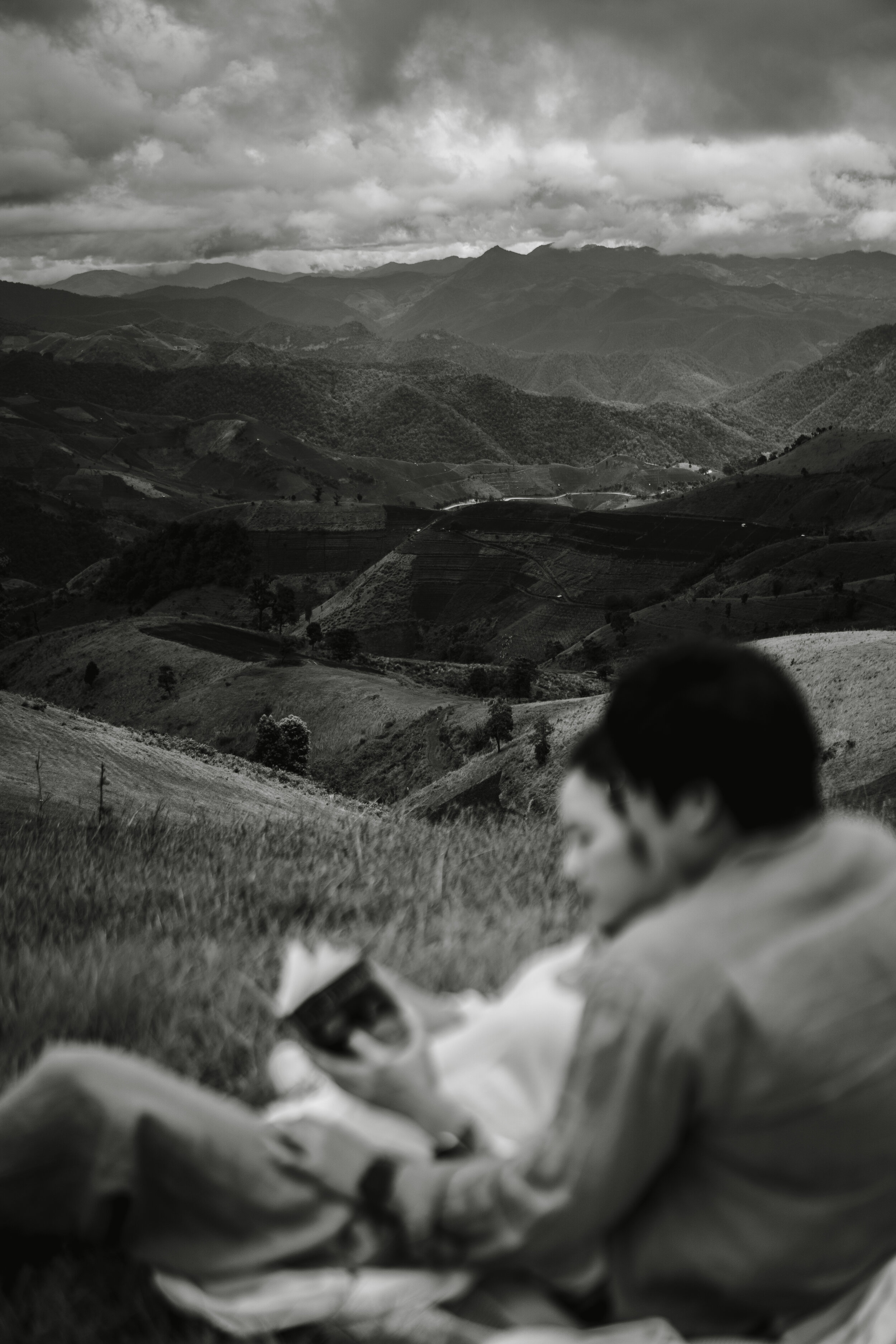

Piyatat Primtongtrakul

For most our marriage, feeling in love just kind of happened because we had a pretty comfortable life. By this I mean that we had privacy, time together, and little competing commitments outside of our marriage. We both studied or worked, and had good groups of friends, but our marriage was always a haven, and no matter how demanding the week was, we were always able to reconnect after a day or two off together.

The challenges started to come with children. As the small storms came with the birth of our first child, we were able to weather them together, with plenty of time left for each other. The second squeezed us some more. And now that our third is over a year old, that we will have time to be alone together at all is no longer a given. We can’t catch up over meals or before bed. We have three other little voices chattering at the table, interrupted sleep that keeps us groggy, and the stress of keeping small kids alive.

In some ways, having children has certainly strengthened our bond; we’ve learned to lean into one another’s strengths, and we can work well as a team. But in other ways—just as a matter of temporal displacement—they’ve impoverished it.

However, we rest in the fact that the substance of our relationship has not been threatened. The vows we’ve made are unconditional, and though it is exhausting, throwing a few kids in the mix doesn’t challenge this. What they do change is the quality, however. When the foundations laid with commitment, sacrament, then it’s time to spruce up the romance too.

*

Karl Ove Knausgaard, the great chronicler of the mundane, notes the challenges of raising three children with his wife. In the second volume of My Struggle, he writes,

Everyday life, with its duties and routines, was something I endured, not a thing I enjoyed, nor something that was meaningful or made me happy. This had nothing to do with a lack of desire to wash floors or change nappies but rather something more fundamental: the life around me was not meaningful. I always longed to be away from it, and always had done. So the life I led was not my own. I tried to make it mine, this was my struggle, because of course I wanted it, but I failed, the longing for something else undermined all of my efforts.

For Knausgaard, the real meaning lay in writing, in his art, and the transcendence that it brought with it. In a literal way, Knausgaard’s children, as well as his wife, become characters who play a role in a story he is telling. He cannot find meaning with or among them, but only behind them, once they are out of the way.

Knausgaard does not believe in God, and so it’s impossible for him to find transcendence and meaning in the everyday, because he himself cannot create that very meaning. Knausgaard is so convinced of God’s absence that his life only takes on significance when he can paste it into a narrative that he alone constructs. His nihilism is beautiful, but it is a hopeless beauty.

Still, for all of the ways Knausgaard leaves significant questions about God and meaning unasked, his observations about the drudgeries of family life remain incisive. Washing floors and changing nappies is not exhilarating. They are acts that eat away at the possibility for transcendence, whether or not it comes from making art or experiencing romance with one’s beloved. For Knausgaard to struggle and prevail, he is required to push through the everyday to reach for the sublime. He has to cultivate art. Though it is excessive and unnecessary for the basest of life, it remains vital.

In a marriage, romance seemed to me to be excessive and unnecessary, but I now see it too remains vital.

*

I am grateful that I experience God’s presence in the world, rather than His absence. In my own day-to-day, the dull work of lugging car seats and picking up discarded toys is a gift from God, just as much as the heights of romance. But because the former comes unbidden, I have to pay more attention to the latter. Romance is not central, perhaps, but it is vital, and it is a garden that requires care and attention if it is to thrive.

This is why, in the past year or so, I’ve come to see the importance of being in love, and I’ve started to learn how to cultivate it. It takes time, of course, and can feel a little awkward. My wife suggested a sunset walk this summer. However, as we meandered through our run-down neighborhood, the bins of old garbage on the right and speeding cars on the left, we found the experience anything but romantic. So, now we plan for dinners out to eat ramen at our favourite spot, which gives us time to talk quietly. Such little moments lighten the deep beauty of marriage with additional joy. Romance is to marriage what flowers are to a vegetable garden. Flowers and romance may not be immediately useful, may not be sufficient to sustain a human body or a lifetime of love, but they have a beauty and loveliness all of their own.

Cole Hartin

Writer & Priest

Cole is an Anglican priest serving in Saint John, New Brunswick with a PhD in theological studies from Wycliffe College. His non-academic writing has been published by The Living Church, Christianity Today, Front Porch Republic, and The Huffington Post.

Photography by Piyatat Primtongtrakul