Leave the Little Demons Behind

Leave the Little Demons Behind

Rachel Pieh Jones

Paintings that are 5,000 years old proliferate inside caves thirty-four miles outside Hargeisa, Somaliland, in an area called Las Geel. Some paintings are possibly as old as 7,000 years. Who painted them and why is unknown. Exactly what they represent is unknown. Who will protect them is also unknown.

Fear of jinn, or mischievous little demons, protected these paintings for centuries as people feared becoming cursed or possessed. Some people said the paintings were drawn with human blood. Goat herders avoided the caves unless sudden thunderstorms drove them inside for protection.

I grew up believing fear was a sin. I was also afraid of everything, which left me in a constant state of guilt. God told Joshua, “Do not be afraid.” Almost every time an angel spoke with a human, the angel first said, “Do not be afraid.” What was I supposed to do with my fear of heights, fear of adults, fear of talking to a stranger on the telephone, fear of a bad grade? My fears were trivial, not like the fears Somali herders felt about jinn, but they were still damning.

As an adult, a longing to be free from fear pushed me toward scary things and I moved to Somaliland in 2003. This felt like one way my faith could work itself out in action and with trembling. What I didn’t yet understand is that facing fear gives faith the opportunity to actually be faith.

*

Somaliland, northern Somalia, is a self-declared breakaway republic. Other than five days in 1960, between when British colonialists granted Somaliland independence and when the British and the Italians (colonizers of southern Somalia) forcibly joined the north and south, Somaliland has never received internationally recognized statehood. What Somaliland has had, however, is relative peace and stability. While the south continues a violent saga of limited government control and the rule of warlords, the north has developed its own democratically-elected government, its own flag, currency, educational system, and its own economic development. Somalilanders are immensely proud of this achievement, as they should be.

I toured Somaliland in 2018 as part of the first-ever Somaliland Marathon, one of three women who planned to participate in this ground-breaking mixed gender sporting event. In the days before the race, we traveled around Somaliland.

One of our first tour stops was a war memorial in downtown Hargeisa. A MIG fighter jet sits on top of a cement platform. Paintings decorate the platform, depicting violent scenes of the 1988 massacre, instigated by southern Somalia against the north. There are heads rolling away from bodies, humans stretching out arms from which the hands have been chopped off. Blood drips and airplanes drop bombs.

While I gazed at the crudely painted horror, a woman came and stood beside me. She said she was a war veteran and pulled out her identity card to prove it. She regaled me with animated stories of the war, of shooting, of her sisters shooting. Her voice grew louder and louder until she was shouting and a small crowd gathered around us. Suddenly, she bent down, grabbed a fistful of dirt, and flung it into the air. As it settled back down over all of us, she said,

“This is my country. My country.”

She meant Somaliland mattered. She meant they deserved independence and recognition. She meant the blood spilled here, thirty years ago this year, mattered.

Other blood had been spilled here, foreign blood, and it had been spilled when I lived in Somaliland, back in 2003. We moved to Somaliland when my husband was recruited to teach at the only functioning university in the country at the time, Amoud University. Within a year, our dream of building the educational system fell apart. Because of three consecutive and brutal murders of expatriates, my family fled the country and moved across the border to Djibouti. Because of those murders and the subsequent harried rush to the airport, I harbored residual anxiety about the safety of Somaliland, even though evidence of peace abounded.

The anxiety manifested itself in tense shoulder muscles, a steady churning in my stomach, and sleepless nights. I regularly glanced over my shoulder and made sure that when our tour group was in public, there was a man between the street and myself. I checked and double-checked the lock on my hotel room door. I flinched when a man in the market yanked on my headscarf. I had nothing to fear and tried to convince myself of this, but fear is a wily creature and not easily tamed.

Even with the fear hovering, I took delight in the stability of Somaliland and the privilege of being able to return, to see how far the region has come since I left fifteen years earlier. Electricity was more widespread and consistent, multi-story buildings created a skyline that obscured some of the bombed remnants of war, evidence of the returning diaspora proliferated in coffee shops, a chocolate chip cookie store, a fried chicken joint, and a stunning library and museum which featured local paintings and handicrafts.

Somalilanders have maintained their stability for nearly three decades without much international intervention or support, some might say because of the lack of international meddling in local affairs. However, one area in which Somaliland’s lack of nationhood is a dangerous detriment is evident at Las Geel.

*

A few days before the marathon, we toured Las Geel. The best protection Las Geel has is its remote location. Thirty-four miles from Hargeisa is not far, but the five-kilometer drive from the paved road to the caves, over extremely rough land, means only the most determined visitor reaches the site. A single metal bar blocks the road at a guard house and barbed wire that is thrust off the walking path provide other semblances of protection. Goat paths and animal droppings litter the area, meaning both herds and their herders have easy access to what should be off limits, if future generations are to experience this unique site.

I had a headache when I toured Las Geel, which could have been blamed on dehydration (it was hot and I hadn’t brought enough water), the drive (the road was so bad it took almost an hour to navigate the 5-kilometers), stress (though Somaliland is safe for tourists, this safety is enforced by requiring visitors to hire armed guards. I find it difficult to relax around AK-47s, even when they are employed with my protection in mind), or my steady state of fearful anxiety that left me jumpy and on the constant lookout.

Or, the headache could have been caused by Las Geel itself, at least according to regional lore. I may have attracted little demons simply by visiting.

Local Somalis knew about the drawings at Las Geel for decades before it gained international attention, but were afraid of the caves. If anyone in nearby villages developed mysterious illnesses, behaved erratically, or suffered from headaches, they were accused of having visited the caves, where they became possessed by jinn, tiny demons.

I didn’t want to endure a zaar, or exorcism, to get rid of my headache, so I swallowed two Tylenol and hiked from my bus to the caves.

In 2002, a French archeological team visited Somaliland, searching for cave drawings. They found this site and in 2003 began excavating it in earnest, joined by Somalis who shared the vision of what a precious national treasure this was.

Dr. Sada Mire is one of those, the only Somali archeologist working in Somaliland. Dr. Mire believes people need culture especially during times of war and strives for the protection of heritage sites.

The area hosts a remarkable volume of drawings in twenty caves and outcroppings. Some estimate as many as 350 figures are represented. The caves overlook the coming together of two riverbeds, mostly dry; but when it rains, the area fills with pools of standing water, which is how it earned its name, the watering place of camels.

The drawings are primarily of humans and animals; cows, dogs, giraffes. Some characters are standing still, others are involved in action: women feed the dogs, calves and humans suck milk, some of the men carry bows and arrows, others appear to be worshipping the animals. The Las Geel staff wanted to make sure I saw one particular scene, of a cow and a bull copulating, and my guide, Khaled mentioned it to me several times, insisted I take a picture.

“Take pictures,” he said. “Take pictures of all the horny animals.”

I asked who had drawn these images, and what their lives had been like.

“These were drawn before Islam came to Somalia,” Khaled, our tour guide said. “There was another name for God, before Allah. Waq. Maybe these are from that time.” He shrugged. “Maybe not.”

Maybe this was a place people came to pray for rain or to make sacrifices or to have sex in private, watched over by the cow and the bull. No pieces of pottery or evidence of buildings or other signs of ancient human life have been found around Las Geel, so little is known about the people who drew these vivid images.

The images are colored in red, white, orange, yellow, and black. Some are still clearly visible, others are faded and difficult to decipher from the rock. Researchers have tried using every available nearby item from dirt, plants, and animal products, to reproduce the colors but have not been able to discover how the paint was created, which adds to the mystery, and the appeal. Here, thousands of years ago, people knew something we cannot discover or understand.

Khaled hovered his hand over an area where the bottom halves of bovine figurines had been washed away. Some areas of the caves are clearly damaged by wind and sand erosion. One rock in a similar historical site even has the year “2000” sadly scrawled directly over some of the drawings.

“That this is unprotected is not just a problem for Somaliland,” Khaled said, “This is a problem for mankind. This is a very important site.”

Without the support provided by becoming a UNESCO World Heritage site, Laas Geel remains vulnerable to human, animal, and natural damage. Somalia has not allocated a budget to protecting sites like Laas Geel, and the government hasn’t ratified the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention, so it does not qualify for UN protection.

One of Dr. Mire’s focuses over the years has been to train locals on protecting the site. The guards here are paid by the Somaliland government, the only site in the country financially supported in this way.

During the civil war in the south, almost all of Somalia’s history was destroyed. From structures, like the Cathedral that had once been the largest in east Africa, to government documents which were used as toilet paper and fuel for fires, little remains of the nation’s heritage.

According to Dr. Mire, “A whole country’s history is almost gone already. So much has been destroyed already. Boxes of documents, Bibles, scrolls, coins, swords, knives, traditional art, jewelry, beads — all of it is gone forever.” (PRI)

Somaliland is eager to celebrate its beauty and heritage, in contrast to the common perception of Somalia as only piracy, famine, and terror. History is a significant part of that beauty, especially for a country struggling to establish itself.

Fear of the jinn had protected Las Geel. Now fear of losing the paintings moved Somalis to push for international recognition. The Somalis I talked with, from the female military vet to the guides at Las Geel, had faith in their ability to succeed as a nation and faith that Allah would guide the process. Their fear and lack of ability to control the caves or their nation forced faith. What else did they have? What else could they do? This faith made them hopeful, it gave them a vision to work toward.

I started to wonder if this was why I’d come to Somaliland for the marathon. I needed to learn what the Las Geel guides and the war vet modeled – to face my fears by reckoning with the truth that I am not in control, and allow that to strengthen faith and provide hope.

*

I devoured this history and the beauty of the remote caves. I laid it over my fear and my personal history in the region and felt the glimmers of healing begin, continue. By coming back to run a race in this country that had sent me running away years ago, I was redeeming my own past. Maybe by listening and sharing the story of Las Geel, in a small way, I could participate in building a new future for Somaliland.

Las Geel is where this heritage collides with the present, a place of discovery and of hope, rooted in history. Now it is up to broader Somalia, UNESCO, and the international community, to help Somaliland protect Las Geel, and other sites like it.

I scrambled around the caves and peered into crannies carved out in the hillside. I gave a television interview in Somali about the beauty of the location and the privilege of being able to tour it. The Las Geel staff, the reporters, our guides, they were fighting Somalis. But not the kind often presented in Western media. They were fighting for history, for the right of their ancestors to be studied, appreciated, and protected. They were fighting for the right of their own country to exist, to be acknowledged.

But until Somaliland is recognized as a nation and ratifies the convention, or until Somalia proper ratifies it, there is little hope for international assistance for heritage sites like this one.

The sun set over the valley below Laas Geel and the temperature noticeably cooled. The stones held their warmth. More trickery from the jinn, of gathering up heat, again to lure a lone traveler into the caves with the promise of a warm and protected night’s sleep.

*

The idea of fighting for the dignity of recognized existence and value nestled deep inside me and struck a discordant contrast with my anxiety, my old fears based on a different Somaliland from fifteen years ago. I leaned against the stones and felt warmth from the sun soak into my back through my marathoner t-shirt.

I was here to fight, too, to fight for the right of women to participate in public sports events. I had been told that women couldn’t run long distances, that it was unsafe for our bodies, my uterus might fall out, I might be rendered infertile. I might collapse. I might bring shame on my husband. But I had run marathons before and knew it was possible. I’d helped to start Girls Run 2, the only all-girls running team in the Horn of Africa. Those girls knew running was possible. I wanted every step I took on that 26.2 mile run to demonstrate that women can run, even in Somaliland.

Instead of the fear and anxiety I had felt when our bus pulled up to Las Geel, a sense of camaraderie filled me. I was here to run and fight for something and to write a new story of goodness over my past story of murder and evacuation. The protectors of Las Geel were there to fight for something. We were all working toward a better future. The feeling nudged aside the negative memories of violence and opened up a space for hope-filled faith.

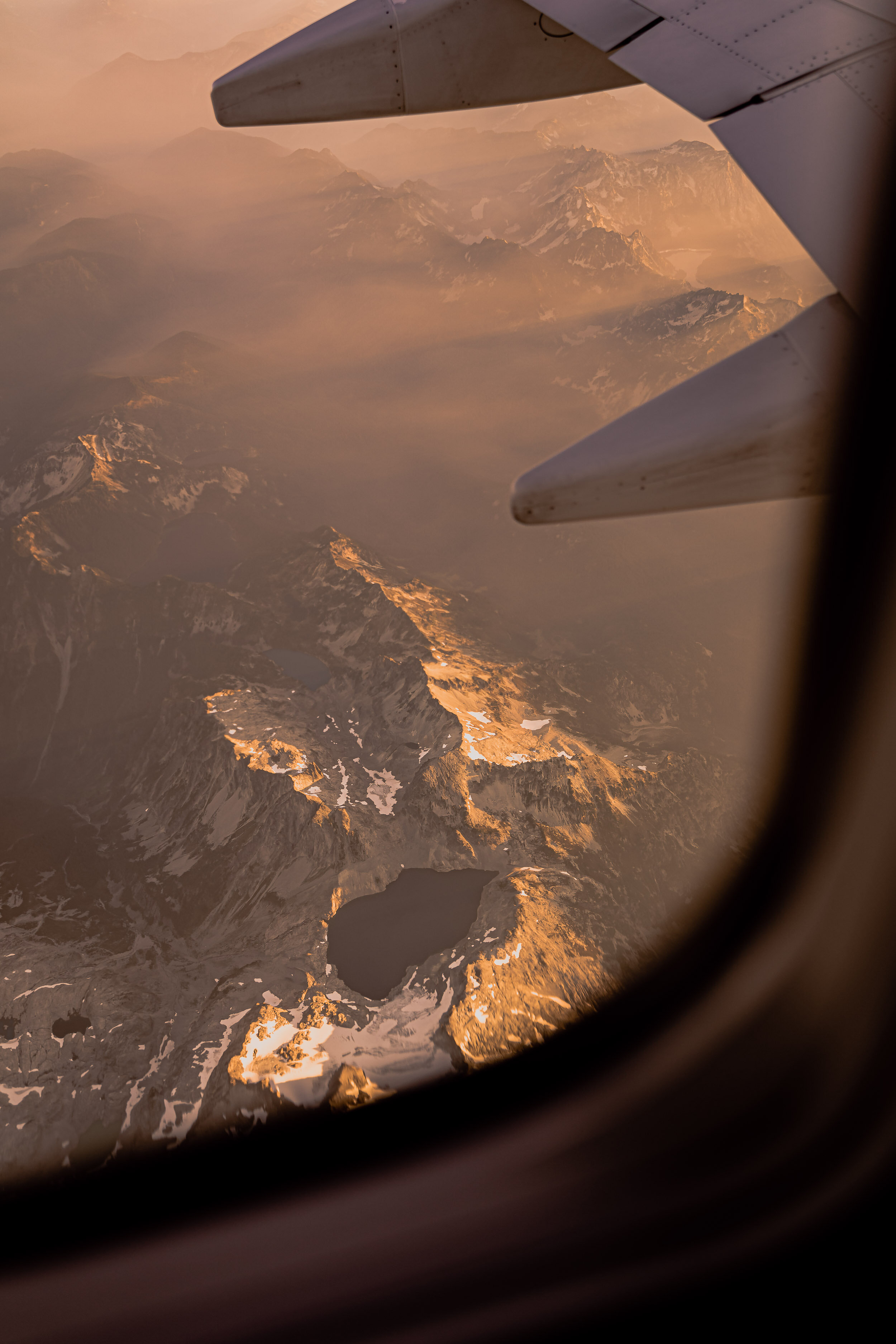

With the setting of the sun, the entire valley below stretched out in desolate, golden beauty. My headache disappeared as I walked back over the rocks to my bus. Maybe the Tylenol kicked in.

Maybe I left the little demons behind.

Rachel Pieh Jones

Writer & Journalist

Rachel Jones has been published in New York Times & Christianity Today

Photography by Zeus Ramirez